Developing a positive community norms campaign can be challenging when you’re looking for new ways to communicate about evolving and critical issues like fentanyl and teen opioid misuse.

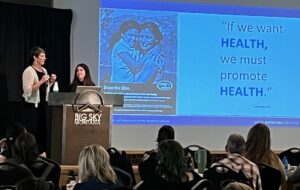

In July, I was honored to co-present at the Montana Summer Institute with the brilliant Sara Thompson, the Montana Institute’s director of communications and training. The summer event, which lasted four days in beautiful Big Sky, was attended by over 300 public health professionals from around the country, all seeking to learn more about using positive community norms to change behavior.

Highlighting positive community norms, also called social norms, can drive positive behavior change while discouraging risky behaviors.

Our presentation, The Question is the Answer, focused on asking new questions and finding new norms in the data to continue to promote the health and positives that already exist in the community.

Here are some of the key takeaways from the presentation and the approaches SE2 has used on a variety of issues, from youth prevention to childhood immunization, in behavior change campaigns across the nation.

- Identify the story you want to tell – what relevant positive norms exist in your community?

- What data is available to you? Are there any surveys that have been done recently, like a state survey?

- Based on the data available, what do you know? What hypothesis could be tested? What new questions could uncover new norms?

- What kinds of messages can you test that would highlight different norms?

- Descriptive norms, “what most people do,” describe what people actually do in a community or social circle. (Example: Most teens have never used fentanyl.)

- Injunctive norms, “what most people think or believe they should do or feel,” describe people’s attitude toward a protective behavior in a community or social circle. (Example: Most teens would support a friend who was trying to quit.)

- Bystander norm messaging says if most people perceive their peers support being active bystanders (in other words, taking action to protect others) then they may be more likely to personally support a peer.

- How are you reaching your intended audience in message testing? Can you partner with local organizations, like school districts, nonprofits, or community centers to distribute a survey?

- Finally, what new norms are appearing in your data?

A key issue is how to promote positive community norms without stigmatizing those who are outside the norm. On the issue of opioids, for example, stigma can be fatal by causing people to use opioids alone, which means no one is there to help if they overdose. Stigma can also deter people from seeking treatment.

One solution we discussed to avoid unintentional stigma was promoting positive bystander behavior. Try using bystander behavior like “x out of x teens support their friends in quitting x,” “x percent of teens would try and stop a friend from using x,” or “most teens would carry naloxone to protect a friend from overdose.” This creates a positive norm without stigmatizing those who have used or are using.

Positive community norms campaigns can help discourage unhealthy behaviors like substance use or violence, and encourage people to change their behavior by correcting misperceptions about what is normal or typical in a group. These campaigns can also promote positive behaviors, attitudes, and the health and hope that already exists in a community.

Positive community norms campaigns can help discourage unhealthy behaviors like substance use or violence, and encourage people to change their behavior by correcting misperceptions about what is normal or typical in a group. These campaigns can also promote positive behaviors, attitudes, and the health and hope that already exists in a community.

For more than 25 years, the Montana Institute has been a leader on this topic, and we’re grateful for our long-time collaboration with the fantastic team there. Their insights have helped inform various prevention campaigns over the years, and we remain committed to sharing and educating people about the positive behaviors and attitudes that can save and change lives.